|

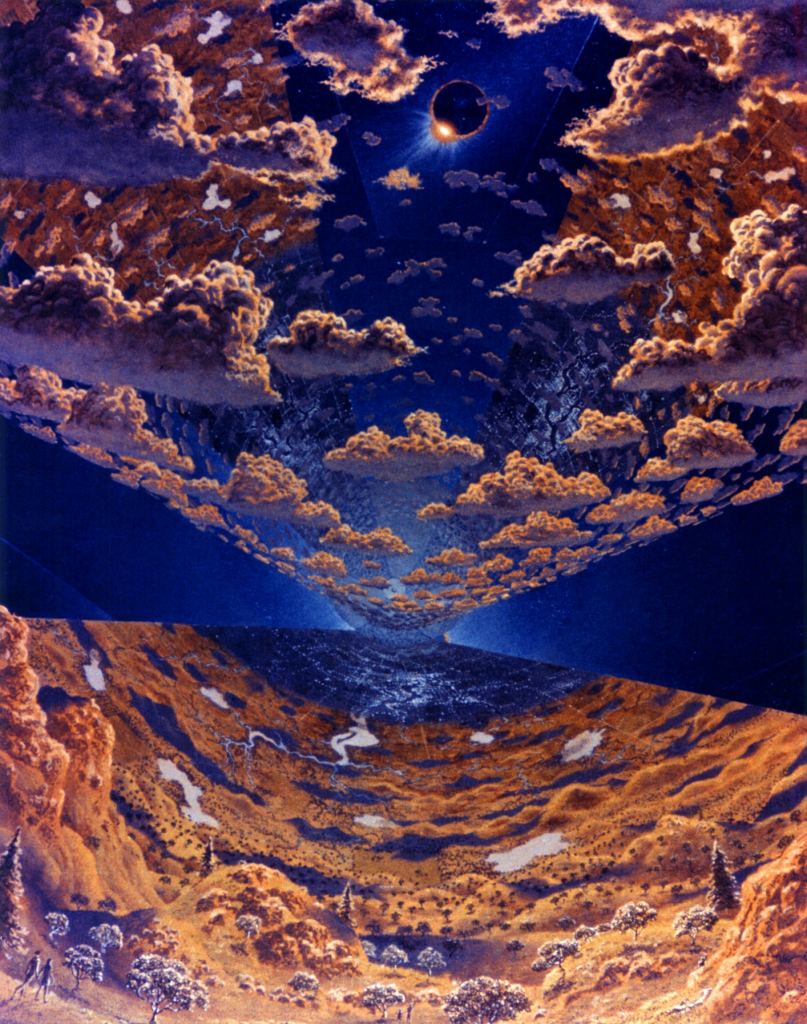

| Imaginary Generation Ship (Credit: NASA) |

The dream of traveling to another star and planting the seed of

humanity on a distant planet… It is no exaggeration to say that it has

captivated the imaginations of human beings for centuries. With the

birth of modern astronomy and the Space Age,

scientific proposals have even been made as to how it could be done.

But of course, living in a relativistic Universe presents many

challenges for which there are no simple solutions.

Of these challenges, one of the greatest has to do with the sheer

amount of energy necessary to get humans to another star within their

own lifetimes. Hence why some proponents of interstellar travel

recommend sending spacecraft that are essentially miniaturized worlds

that can accommodate travelers for centuries or longer. These

“Generation Ships” (aka. worldships or Interstellar Arks) are spacecraft

that are built for the truly long haul.

The logic behind a generation ship is simple: if you can’t travel

fast enough to get to another star system within a single lifetime,

build a vessel large enough to carry everything you would possibly need

for a long voyage. This would entail making sure that a ship has a

reliable propulsion system that can provide steady thrust during

acceleration and deceleration and the necessary amenities to provide for

several generations of humans.

On top of all that, the ship would need to be able to

ensure that its crews had food, water, and breathable air – enough to

last for centuries or even millennia. In all likelihood, this would mean

creating a closed-system microclimate inside the ship, complete with a

water cycle, a carbon cycle, and a nitrogen cycle. This will allow for

food to be grown and for water and air to be continuously recycled.

Reaching the Nearest Stars

The closest star to our Solar System is Proxima Centauri, an M-type

(red dwarf) main sequence star located roughly 4.24 light-years away.

This star is part of a triple star system that includes the Alpha

Centauri system, a binary consisting of a main sequence Sun-like star (a

G-type yellow dwarf) and a main sequence K-type (orange dwarf) star.

In addition to being the closest star system to our own, Proxima Centauri is also the home of the closest exoplanet to Earth – Proxima b.

This terrestrial (aka. rocky) planet – whose discovery was announced in

2016 by the European Southern Observatory (ESO) – is about the same

size as Earth (1.3 Earth masses) and orbits within the circumsolar habitable zone of its star.

The next closest exoplanet that orbits within its star’s HZ is Ross

128 b, an Earth-sized exoplanet that orbits a red dwarf star some 11

light-years away. The next closest Sun-like star is Tau Ceti, which is

just under 12 light-years away and has one potentially-habitable

candidate (Tau Ceti e). In fact, there are 16 exoplanets within 50 light-years of Earth that could support life.

But as we explored in a previous article, traveling to even the nearest star

would take a very long time and require a tremendous amount of energy.

Using conventional means of propulsion, it could take between 19,000 and

81,000 years to get there. Using proposed methods that have been tested

but not yet built (like nuclear rockets), the travel time is narrowed to about 1000 years.

There are proposed methods that are capable of reaching the nearest

stars within a single lifetime, such as directed-energy propulsion – for

example Breakthrough Starshot. For this concept, a light sail and gram-scale spacecraft could be accelerated to 20% the speed of light (0.2 c),

thus making the journey to Alpha Centauri in just 20 years. However,

Starshot and similar proposals are all uncrewed concepts.

Beyond this, the only possible methods for sending human beings to

another star system are either technically feasible (but undeveloped) or

entirely theoretical (like the Alcubierre Warp Drive).

With that in mind, many scientists have drafted proposals that would

forsake speed and instead focus on accomodating crews during the long

voyage.

Examples In Fiction

The earliest recorded example appears to have been made by engineer and science fiction writer John Munro’s in his novel A Trip to Venus (1897). In it, he mentions how humanity may become an interstellar species one day:

“[W]ith a vessel large enough to contain the necessaries of life, a select party of ladies and gentlemen might start for the Milky Way, and if all went right, their descendants would arrive there in the course of a few million years.”

The concept was addressed in more detail in the 1933 science fiction novel When World Collide,

which was co-authored by Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer. In this story,

Earth is about to be destroyed by an exploding star, which forces a

group of astronomers to create a massive ship carrying a crew of 50,

along with livestock and equipment, to a new planet.

Robert A. Heinlein also explored the physical, psychological and

social effects of a generation ship in one of his earliest novels, Orphans of the Sky.

The story was originally published as two separate novellas in 1941 but

was re-released as a single novel in 1963. The ship in this story is

known as the Vanguard, a generation ship that is permanently adrift in space after a mutiny led to the deaths of all the piloting officers.

Generations later, the descendants have forgotten the purpose and

nature of the ship and believe it to be their entire Universe. The bulk

of the crew still lives within the cylinder, but a separate group of

“muties” (which alternately means they are mutants or mutineers) live in

the upper decks where the gravity is lower and exposure to radiation

has caused physical changes.

Arthur C. Clarke’s Rendezvous with Rama

(1973) is arguably the best-known example of a generational ship in

science fiction. Unlike other fictional treatments of the concept, the

vessel in this story was extra-terrestrial in origin! Known as Rama,

this massive space cylinder is a self-contained world that is carrying

the “Ramans” from one side of the galaxy to the other.

The story opens as a crew from Earth is dispatched to

rendezvous with the ship and explore the interior. Inside, they find

structures arranged like cities, transportation infrastructure, a sea

that stretches around the center, and horizontal trenches that act as

windows. As the ship gets closer to the Sun, light floods in and the

machinery begins to come to life.

Eventually, the human astronauts conclude that the buildings are

actually factories and that the ship’s sea is a chemical soup that will

be used to create “Ramans” once it reaches its destination. Ultimately,

though, our Solar System is just a stopover on their journey and that

this is how the Ramans seeds the galaxy with their species.

In Alastair Reynold’s Chasm City (2001) – which is part of his Revelation Space

series – much of the story takes place aboard a series of large,

interstellar spacecraft. These ships are traveling to 61 Cygni, a binary

star system consisting of two K-type orange dwarfs, to colonize a world

that is known throughout the series as Sky’s Edge.

These ships are described as cylindrical and rely on antimatter

propulsion to travel at relativistic speeds. In addition to carrying a

compliment of cryogenically-frozen passengers, these ships maintain a

crew in waking conditions and have all the necessary facilities and

equipment to keep them entertained. These include personal quarters,

mess halls, medical bays, and recreation centers.

In 2002, famed science fiction author Ursula K. LeGuin

released her own take on the effects of inter-generational space

travel, titled Paradises Lost. The setting for this story is the Discovery,

a ship that has been traveling through space for generations. As those

who remember Earth begin to die off, the younger generations begin to

feel like the ship is more tangible to them than either the lore about

their old homeworld or their destination.

Eventually, a new religion emerges called “Bliss” that teaches that the Discovery (“spaceship

heaven” to the faithful) is actually bound for eternity rather than

another planet. This religion is being embraced to the dismay of the

older generation who fear their children will never want to leave the

ship once it arrives. This story was adapted into an opera in 2012 as

well.

The 2011 novel Leviathan Wakes by James S. A. Corey (and subsequent installments in the Expanse

series) features a generation ship named “Nauvoo”. This vessel is being

built by a group of Mormons so they can travel to another star system

and colonize there. The Nauvoo is described as being massive,

cylindrical in shape, and rotates to generate artificial gravity for its

crew.

In Kim Stanley Robin’s Aurora

(2015), the majority of the story takes place aboard an

eponymously-named interstellar starship. Robinson describes a vessel

that uses two rotating torii to simulate gravity while the people live

in a series of Earth-analog environments. Their ultimate destination is

Tau Ceti, a Sun-like star located 12 light-years from Earth, where they

intend to colonize an exomoon that orbits Tau Ceti e.

The ship is described as an Orion-class vessel that

uses the controlled explosion of thermonuclear devices to generate

propulsion, along with an electromagnetic array used to launch it from

the Solar System. In Robinson’s signature style, considerable attention

is also dedicated to how the colonists maintain a careful balance aboard

their vessel and the psychological effects of multi-generational

travel.

Proposals

Multiple proposals have been made by scientists and engineers since

the early 20th century. Many of these proposals were presented in the

form of studies while others were popularized in science fiction novels.

The earliest known example was the 1918 essay “The Ultimate Migration” by rocket-pioneer Robert H. Goddard (for whom NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center is named).

The crew would spend the centuries-long journey in suspended

animation, with the pilot being awakened at intervals to make course

corrections and maintenance. As he wrote:

“The pilot should be awakened, or animated, at intervals, perhaps of 10,000 years for a passage to the nearest stars, and 1,000,000 years for great distances, or for other stellar systems. To accomplish this, a clock operated by a change in weight (rather than by electric charges, which produce too rapid effects) of a radiation substance, should be used… This awakening would, of course, be necessary in order to steer the apparatus, if it became off its course.”

He also envisioned that atomic energy could be used as

a power source; but failing that, a combination of hydrogen and oxygen

fuel, as well as solar energy, would suffice. Based on his calculations,

Goddard estimated that these would be sufficient to get the ship up to

speeds of 4.8 to 16 km/s (3 to 10 mi/s), which works out to 17,280 km/h

to 57,936 km/h (10,737 to 36,000 mph) or 5% to 20% the speed of light.

Konstantin E. Tsiolkovsky, the “father of astronautic theory”, also

addressed the idea of a multi-generational spaceship in his essay “The

Future of Earth and Mankind” (1928). Tsiolkovsky described a space

colony (a “Noah’s Ark”) that would be self-sufficient and where crews

were kept in wakeful conditions until they reached their destination

thousands of years later.

Another early description of a generation ship is in the 1929 essay “The World, The Flesh, & The Devil”

by J. D. Bernal (inventor of the “Bernal Sphere”). In this influential

essay, Bernal wrote about human evolution and it’s future in space,

which included vessels that we would today describe as “generation

ships.”

In 1946, Polish-American mathematician Stanislaw Ulam proposed a

novel idea known as Nuclear Pulse Propulsion (NPP). As one of the

contributors to the Manhattan Project, Ulam envisioned how nuclear

devices would be repurposed for the sake of space exploration. In 1955,

NASA launched Project Orion for the purpose of investigating NNP as a means for conducting deep-space voyages.

This

project (which officially ran from 1958 to 1963) was led by Ted Taylor

at General Atomics and physicist Freeman Dyson from the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. It was abandoned after the Limited Test Ban Treaty (signed in 1963) established a permanent ban on nuclear testing in Earth orbit.

In 1964, Dr. Robert Enzmann proposed the most detailed concept for a generation ship to date, thereafter known as the “Enzmann Starship“.

His proposal called for a ship that would use deuterium fuel to

generate fusion reactions to achieve a small percentage of the speed of

light. The craft would measure 600 meters (2000 feet) in length and

accommodate an initial crew of 200 (with room for expansion).

During the 1970s, the British Interplanetary Society conducted a feasibility study for interstellar travel known as Project Daedalus.

This study called for the creation of a two-stage fusion-powered

spacecraft that would be able to make the trip to Barnard’s Star (5.9

light-years from Earth) in a single lifetime. While this concept was for

an uncrewed spacecraft, the research would inform future ideas for

crewed missions.

For example, the international organization Icarus Interstellar has since attempted to revitalize the concept in the form of Project Icarus.

Founded in 2009, Icarus’ volunteer scientists (many of whom have worked

for NASA and the ESA) hopes to make fusion propulsion and other

advanced propulsion methods a reality in the 21st century.

Studies

have also been conducted that have considered antimatter as a means of

propulsion. This method would involve colliding atoms of hydrogen and

antihydrogen in a reaction chamber, which offers the benefits of

incredible energy density and low mass. For this reason, NASA’s Institute for Advanced Concepts (NIAC) is researching the technology as a possible means for long-duration missions.

Between 2017 and 2019, Dr. Frederic Marin of the Astronomical Observatory of Strasbourg

conducted a series of highly-detailed studies on the necessary

parameters for a generation ship – including minimum crew size, genetic

diversity, and the size of the ship. In all cases, he and his colleagues

relied on a new type of numerical software (called HERITAGE) that they created themselves.

For the first two studies, Dr. Marin and his colleagues conducted simulations that showed that a minimum crew of 98 (max. 500) to be coupled with a cryogenic bank of sperm, eggs, and embryos in order to ensure survival (but avoiding overcrowding) as well as genetic diversity and good health upon arrival.

In the third study,

Dr. Marin and another team of researchers determined that a generation

ship would need to measure 320 meters (1050 feet) in length, 224 meters

(735 feet) in radius, and contain at least 450 m² (~4,850 ft²) of

artificial land for the sake of agriculture. This land would also ensure

that the ship’s water and air would be recycled as part of a

microclimate.

Advantages

The main advantage of a generation ship is the fact it can be built

using proven technology and will not have to wait on considerable

advancements in technology. Also, the central aim of the concept is to

forego the issue of speed and propellant mass to ensure that a crew of

human beings can eventually colonize another star system.

As we explored in a previous article,

a generation ship would also fulfill two major goals of space

exploration, which are to maintain a human colony in space and permit

travel to a potentially habitable exoplanet. On top of that, a crew that

numbers in the hundreds or thousands would multiply the chances of

successfully colonizing another planet.

Last, but not least, the spacious environment of a generation ship

would allow for multiple methods to be pursued. For example, part of the

crew could be kept in waking conditions for the duration of the journey

while another part could be kept in cryogenic suspension. People could

also be revived and return to suspension in shifts, thus minimizing the

psychological effects of the long-duration journey. Unfortunately, that’s where the advantages end and the problems/challenges begin.

Disadvantages

The most obvious disadvantage of a generation ship is the sheer cost

of constructing and maintaining such large spaceships, which would be

prohibitive. There are also the dangers of sending human crews into deep

space for such extended periods of time. On a voyage that would take

centuries or millennia, there is the distinct possibility that the crew

will succumb to feelings of isolation and boredom and turn on each

other.

Then there are the physiological issues that a multi-generational

journey through space could entail. It is well-known that the radiation

environment in deep space is significantly different than the

environment on Earth or in low Earth orbit (LEO). Even with radiation

shielding, long-term exposure to cosmic rays could have a serious impact

on crew health.

While cryogenic suspension could help mitigate some of these issues,

the long-term effects of cryogenics on human physiology is not yet

known. This means that extensive testing would be needed before such a

mission could ever be attempted. This only adds to the overall moral and

ethical considerations that this concept entails.

Last, there is the possibility that subsequent technological progress

will lead to the development of faster and more advanced starships in

the meantime. These ships, departing Earth after much later, could be

able to overtake the generation ship before it ever reached its

destination – thus making the entire journey pointless.

Conclusions

Given the sheer cost of building a generation ship, the risks of

making such a long journey, the number of unknowns involved, and the

possibility that it would be rendered pointless by the advancement of

technology, one has to ask the question: is it worth it? Unfortunately,

like so many questions pertaining to multi-generational space travel,

there is no clear answer.

In the end, if the resources are available and the will to do it is

there, human beings may very well attempt such a mission eventually.

There will be no guarantee of success and, even if the crew successfully

makes it to another star system and colonizes a distant planet, it will

be millennia before anyone on Earth hears from their descendants.

Under the circumstances, it would seem more sensible to just wait on

further technological advances and try to go interstellar later.

However, not everybody may not be so willing to wait, and history tends

to remember those who defy the odds and take risks. And as ventures like

Mars One have shown us, there is no shortage of people willing to risk their lives for the sake of colonizing a distant world!

We have written many articles on the subject of Generation Ships here at Universe Today. Here’s What’s the Minimum Number of People you Should Send in a Generational Ship to Proxima Centauri? and How Big Would a Generation Ship Need to be to Keep a Crew of 500 Alive for the Journey to Another Star?, The Most Efficient Way to Explore the Entire Milky Way, Star by Star, and Pros and Cons of Various Methods of Interstellar Travel.

Sources:

- Wikipedia – Generation Ship

- Wikipedia – Interstellar Ark

- Strange Paths – Interstellar Ark

- SFF – Themes: Generation Ships

- Mashable – The interstellar dream is dying

- Centauri Dreams – Worldships: A Interview with Greg Matloff

- Icarus Interstellar – Project Hyperion: The Hollow Asteroid Starship – Dissemination of an Idea

- HERITAGE: a Monte Carlo code to evaluate the viability of interstellar travels using a multi-generational crew, Marin, Frederic. JBIS, vol. 70, no. 5-6, 2017

- Computing the minimal crew for a multi-generational space journey towards Proxima Centauri b, Marin, F., Beluffi, C. JBIS, vol. 71, no. 2, 2018

- Numerical constraints on the size of generation ships from totalenergy expenditure on board, annual food production and spacefarming techniques, Marin (et al.). JBIS, vol. 71, no. 10, 2018

Hiç yorum yok:

Yorum Gönder